If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can get thoughts and musings about personal finance and whatever else I find interesting straight to your inbox by clicking here:

I’ve been working for early-stage startups since I got out of college, and as is fashionable these days, I’ve become more interested in venture and angel investing recently, and decided I wanted to try it out for myself. With the IPO markets so hot right now, angel investing starts to look like a really attractive investment because the earlier you get into a company, obviously the better returns you can get, but it’s also an outrageously high-risk investment, and the majority of angel investments are likely to go to zero.

That said, companies like AngelList, and the rise of investing syndicates and crowd-sourced funding rounds has made angel investing surprisingly easy. I’m new to this stuff myself, so take my thoughts with a grain of salt, and above all, proceed with caution, because you’re probably going to lose money.

In order to understand how to angel invest in a sane way (i.e., slightly more rationally than gambling), I decided that I wanted to understand more about how venture funds actually operate, so that I can more effectively manage my own expectations.

How do venture funds measure themselves?

Venture firms measure themselves a little bit differently than the way standard stock index performance is measured. While understanding these isn’t critical to actually making an angel investment, I find that it’s useful to have a base knowledge around VC-oriented metrics, because it helps inform expectations around investment horizons and goal-setting. One option for angel investing is actually to invest in a fund, and knowledge of these metrics can be useful tools to evaluate the quality of a fund. There are a handful of metrics that VCs talk about, but some of the ones you’re likely to come across as you learn more about venture are:

Distributions to Paid In (DPI): DPI is probably the most important metric for a venture fund, because it boils down to the most fundamental brass tacks of the fund’s cash flows. Paid in capital refers to the amount of money that investors (called Limited Partners or LPs) have put into the fund, and distributions are what get paid out to investors when gains are realized. The DPI metric measures how much of the cash in the fund actually makes it back out to investors. This number starts at 0 at the inception of the fund, and rises over time. DPI of 1 implies break-even: the money that came in was paid out dollar for dollar. Anything less than 1, and the fund lost money. It’s worth noting that this metric really matters most at the end of the fund’s life, and a DPI under 1 at the 5-year mark doesn’t mean the fund won’t be successful by the end of its lifespan (usually somewhere in the 7-10 year range).

Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC): MOIC is actually closely related to DPI, but tracks both realized outcomes (where a company has had a liquidity event, could be success or failure), as well as unrealized outcomes (companies that are still trying to make it). The multiple in this case refers to the overall return of the fund. If you have an MOIC of 3x, for every $1 invested, your dollar is worth $3 on paper. At the end of a fund’s life, MOIC and DPI should arrive at the same number, but throughout the life of a fund, the multiple will likely jump around as funding rounds and liquidity events occur. This number is often used to evaluate the performance of a fund along its lifespan.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR): The best way to think about IRR is that it’s effectively the rate of return that the fund is tracking towards. The reality is that IRR is a fairly complex computation of cash flows from investments as they are realized and based on funding rounds that provide additional information about valuations along the way. As a result, IRR can look really high at the start of a fund’s life when all of the investments still look like they could be the next Facebook, and IRR will often head steeply downwards in the first several years, as reality sets in and it becomes clear that the fund’s Facebooks are actually Clinkles. It becomes a really useful metric to look at towards the end of a fund’s life, as it represents the average annual return over the life of the fund.

Venture is about beating the market, but by less than you might think

Understanding these definitions a bit better makes it easier to get a sense for the mechanics of how venture funds operate, so let’s switch to looking a bit at why venture is an attractive asset class. In order to do that, we need to take a look at the broader stock market first.

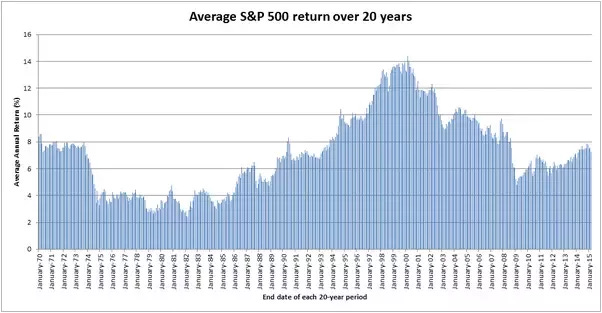

If you bought $1000 of the S&P 500 index, and held onto it for 10 years, on average, you’d end up with somewhere around $2000 after those 10 years. The average annual return would land you somewhere in the 7.5% range (granted, returns in recent years have been way higher than this, but over the life of the S&P 500 index, returns generally tend towards this point).

Funds focused on different stages of a company’s life have different metrics that they’re trying to hit, but for an early-stage fund, they’re typically aiming for a 3x-4x DPI. For every $1 you invest, the fund wants to return $4 to you. If we consider that most funds operate on a 10-year timescale, and we compare it to the 2x performance than a 10-year investment in the S&P500 provides, we’re really only trying to beat the market by about 2x, or roughly 15% annual returns. If you look at Pitchbook data for angel and early-stage funds at fund vintages over the past 20 years, you’ll find that the average IRR of those funds is, in fact, very close to 15%.

At the 10-year mark, the allure of venture makes sense, but it’s not earth-shatteringly better than the market. However, if you blow out the timescale to 30 years, and we look at the relative performance to the stock market of a 15% IRR fund, the performance difference becomes extremely attractive.

Hot diggity dog! Making 7x my money sounds nice. But it turns out: this shit is hard. I mean, it looks less hard when you look at recent exits like Snowflake, Airbnb, and even lesser known companies like JFrog (who have been wild successes in their own right). Sutter Hill’s $5M series A, plus the subsequent follow-on pro rata investments in later rounds resulted in a $12B payout. That’s a whopping 2400x multiple on their investment. The reality of investing, though, is that the likelihood of picking a Snowflake from a pool of investment opportunities is infinitesimally small at the seed stage, or even at the A stage. Finding that needle in a haystack requires a combination of broad visibility across the spectrum of opportunities, having an investment thesis that is spot-on, finding the right team to execute, and a heaping helping of luck.

VCs are certainly looking for those one-in-a-million shots to be the next Snowflake, but they know they’re not going to hit it out of the park every time (and in fact, Pitchbook offers a histogram of the success of a fund called a batting average, which looks at how many portfolio companies in a fund went bankrupt, versus had an exit in various ranges -- 0-1x, 1-5x, 5-10x, 10-20x, etc.) A lot of these charts skew towards bankruptcies and the 1-5x returns. It’s just the nature of the startup world. Per CB Insights, about 1% of seed-funded companies make it to the $1B mark. That’s actually a pretty good shot at a huge outcome, all things considered, but you have to also consider that only 0.05% of startups actually raise seed capital. Obviously this ignores macro dynamics (read: pandemics), and probably varies from sector to sector, but interesting to think about, nonetheless.

Enough talk! Let’s angel!

Hold your horses. There’s a whole bunch of important implications here about how you might strategize your plan to do angel investing. The first is recognizing that even though firms want to get to that magical 15% IRR mark, many don’t make it there. Funds are able to improve their changes though heavy diversification. They come up with investment theses, designed to improve their chances of finding home runs, but a lot just comes down to simple probability, and good old modern portfolio theory. Diversify your bets, limit your losses.

There are lots of articles about the percentage of the rate of success of venture investments, and there’s a lot of “rules of thumb” about venture success. The rule of thirds suggests that in a well-allocated portfolio, a third of venture investments will go to zero, a third will make their principal back, and a third will produce the majority of the returns. Other data suggests that about 60% of startups fail after raising a seed, and only about 3% of an overall portfolio will have 10x+ returns. The numbers are certainly against us. This suggests that we need to make a reasonably substantial number of investments in order to diversify appropriately.

The other harsh reality is that angel checks are not insubstantial in most cases. If you invest directly in a friends-and-family round, it’s likely that you’re going to need to plunk down a $10-25K check. If we assume that we need 20-30 investments to diversify our portfolio substantially, we’re talking about like $250K of liquid assets just for angel investing. However, there are a number of venture crowdfunding sites out there, the most notable being AngelList. In the case of AngelList investments, there are usually minimum check sizes, but they’re typically in the $1000-$5000 range, which takes that asset requirement from $250K to about $50-75K.

That said, if $50K is a substantial portion of your investable assets, you might want to think twice about angel investing. The inherent risk with angel investing is also why the government generally requires you to be “accredited” in order to invest in high-risk assets (more on this in the next post). With every investment on AngelList you need to check a box that basically says “startups are risky, and this investment could very easily go to zero, so don’t invest any money you can’t afford to lose,” and they’re right. Everybody’s got a different risk tolerance, so you need to use your best judgment, but I generally wouldn’t feel comfortable having more than 5-10% of my net worth wrapped up in extremely high-risk assets. If I extrapolate that out, if you’re playing with your own money, you should probably be careful if your investable assets are less than $750K or so. Or at least recognize that you’re doing more gambling than investing.

Next time we’ll start digging into the mechanics of actually writing checks as angel investments, and building up enough working knowledge to do what we all want to do here: set some money on fire in the form of seed-stage investments!