Evaluating an investment on Angel List

If you’re still with me on this angel investing series, hopefully it either means I produce engaging content, or you’re hellbent on making some angel investments (or maybe you’re just enjoying watching me set money on fire). In this installment, we’re going to take a look at how deals are actually structured (I’m going to use AngelList as an example, since that’s where most of my deal flow comes from).

Understanding how AngelList presents an investment opportunity

The first time you look at an investment opportunity on AngelList, if you’re not familiar with what you’re looking at, it’s probably going to be a little confusing to interpret. Honestly, I hope if you’ve gotten this far, you’ve educated yourself enough that you don’t need any of the information I’m about to provide, and the only folks who are actually getting stuff out of this are people who haven’t yet decided to take the plunge.

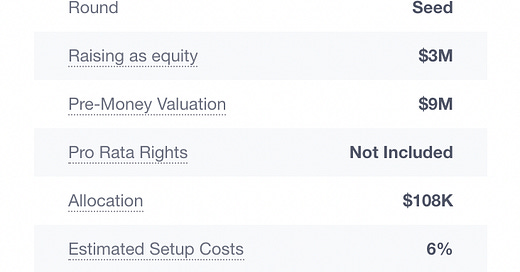

AngelList provides a whole bunch of useful information to get a snapshot of the deal you’re looking at:

Round: If you’ve been around the startup world, this one is pretty self-explanatory. You’ll usually see something like Seed, A, B, etc. You might see something like Seed+ or A1 or something like that, which usually indicates that the round is an extension. That additional detail is useful when deciding if you want to invest, because oftentimes extensions are done because there’s more funding needed before the company really feels like it’s hit appropriate milestones to raise the next round for real. It could also be a mechanism to set an intermediate price ahead of a round, as well. There are lots of reasons an organization might raise an extended round, some good, some bad.

Raising as X: The amount here will indicate how much money is being raised in the round in aggregate. This doesn’t mean that they’re raising that much from AngelList, but that it’s the full size of the round. I almost care less about this number than I do the mechanism by which they’re raising. For seed investments, this will often say “raising as equity” or “raising as SAFE.” In the event that they’re raising as equity, the implication is that this is a dilutive round for the business, and the SPV is acquiring stock directly from the company. For many seed rounds of financing, the funding is actually done as convertible debt.

The SAFE refers to the Standard Agreement For Equity that was popularized by Y-Combinator. It functions very similarly to convertible notes (which will display as “raising as debt”), in that you’re providing money to the company now, for the promise of equity at a particular price point later. That particular price point is known as the “cap” for the note. The difference is extremely important, especially if you’re thinking about timing from a capital gains perspective. With a SAFE, you’re not actually buying equity, you’re paying for the promise of equity later, and the SAFE will convert to equity in the next priced round (meaning the next round where money is exchanged directly for equity). This also impacts the timer to claim the purchase as qualified small business stock (though being totally candid, if you’re buying through AngelList, you probably don’t have enough access to the business to ensure that your purchase is QSBS), so dates matter a lot here.

Cap: If the deal is being raised as a SAFE, there’s a handful of rows you may or may not see. You’ll almost certainly see one labeled “Cap” or “Post-money Cap.” The cap is essentially the maximum price that you will pay when your stock converts to equity in a subsequent priced round. So if you invest $2000 into a deal with a cap of $12M, a couple things could happen when the company raises their A round. Possibility 1 is that they raise money at a price lower than the cap, say $10M. In that case, your $2000 converts to stock at a $10M valuation, and you end up owning .02% of that $10M company (give or take, given setup costs and such). Possibility 2 is that the company raises money at $12M or more. If they raise at $15M, for example, your SAFE says you will not have to pay more than $12M, so you actually get a good deal here. Instead, you own .016% ($2000 divided by $12M), but since the company is actually worth $15M, your stock is actually worth $2500, and you just made $500 in sweet, sweet, paper, totally illiquid, non-saleable gains. Congratulations. It’s also worth noting that you might see SAFEs that are uncapped, which is kind of a crappy deal for the investor. You don’t get to buy your stock today, and you’re also buying it at a completely unknown price. But if the deal is hot, maybe it’s worth taking that risk.

Discount: Depending on the structure of the deal, you might also see a discount rate on a SAFE-based round. When a note contains a discount term, what it says is that whatever the price of the next round, where your SAFE will convert to equity, you’re going to get a discount at that rate. This might be paired with a cap, and it might not. If you have a cap, as well, it’s a pretty darn good deal for the investor. If the company does really well, you get the benefit of both a lower price, due to the cap, and also a discount on top of that. It’s generally a good thing for the investor.

Pre-Money Valuation: If you’re buying equity, and this is a priced round, the pre-money valuation will tell you the valuation of the company before the financing. So if the company is raising $3M at a $12M pre-money valuation, the post-money valuation will be -- you guessed it -- $15M. This is helpful information because what it tells you is how much equity the company is giving up to raise this round. $3M on a $15M post-money valuation is a very healthy round, because the equity being sold is 20% of the company. The types of firms that lead investments will typically demand a certain amount of skin in the game for the investment to be worth it to them, and that ballpark tends to be in the 15-25% range. If you see dilution way higher than 25%, you probably want to tread carefully, because it means the company is probably desperate for cash, and if it’s way less than 15%, you could be overpaying for the equity, and while it might be a hot company, you may be implicitly assigning less risk to the investment than is appropriate.

Pro-Rata Rights: This is more common for lead investors, but it’s rare that I see syndicated deals that have pro-rata rights. Pro-rata rights boil down to getting the right to maintain your level of investment in subsequent rounds of funding. Since subsequent rounds usually bring on new investors, existing investors risk getting diluted out of their position if a later round of funding adds a ton of new equity. To protect themselves from this, many lead investors will require pro-rata rights, which allow them to purchase stock at the round’s price to maintain their level of investment. To take a concrete example, let’s assume you purchase 1% of a company in their seed round for $100,000 (which implies a valuation of $10M). You have pro-rata rights, and a year later, the company decides to raise a round of funding, and gets a terms sheet to raise $10M at a $50M post-money valuation. This will add 20% of dilution, since this new stock is created to facilitate the $10M raise. You could waive your pro-rata rights, and then you’d end up owning 0.8% of a $50M company, or you could double down on your investment and choose to exercise your pro-rata, which would require you to pony up an additional $100,000 (because after dilution, you would have the right to purchase .2% at the $50M price) to maintain your 1% stake.

Once you get past this point in the details of the investment, you’re starting to veer into the more boilerplate-y parts of the deal.

Allocation: This is the actual amount that is available to the syndicate. While I don’t have concrete stats on the average check sizes that AngelList syndicate participants are writing, it generally seems like a lot of them tend to be fairly close to the minimum, which is unsurprising, since diversification is usually a good thing in venture. Allocation sizes can vary wildly, though I find that most syndicates tend to be fairly consistent in their allocation sizes, which are often in the $100-200K range.

Estimated Setup Costs: On AngelList, setup costs for a new SPV are $8000, and that amount gets spread proportionally across all of the LPs. As a result, the percentage that AngelList displays is a function of the allocation size. Larger allocations, lower setup costs for each LP. Smaller allocations, larger setup costs for each LP. On the bright side, it’s a one-time fee, and not an annual management fee like a fund charges.

Syndicate Lead’s Investment: And finally we’ve arrived at the real kicker, and why syndicating deals on AngelList can be a really good deal for syndicate leads. Getting a syndicated deal setup has overhead, for sure, but the lead’s investment is almost always around, or even less than the actual minimum investment from the LPs. The implication is that they’re actually putting in a very minimum amount of their own skin in the game (this is not always true, but is frequently true), and most of the money they’re making is on the deal structure itself, and receiving carried interest on future gains. Obviously, leads don’t want to syndicate bad investments, because they don’t make money if you don’t make money, but most of their money will be made off of your investments, not their own. It’s good to keep in mind, but a bit part-and-parcel in the pay-to-play venture capital world.

Evaluating a deal

This is the hard part. I’ve seen really popular deals appear and be gone inside of a day. That’s pretty rare, but it happens. Sometimes an investment opportunity is on a tight timeline, because the company is finishing up their round, and wants to close in a short number of days. The reality of angel investing, and venture, generally, is that it’s very time-sensitive, and a deal happens when it happens. In practice, most investment opportunities seem to last for at least a few days, sometimes a week. Some linger on and on, and if I see an investment opportunity that’s hanging around for a while, it’s usually an indicator to me that the company is having a hard time completing its raise. There’s lots of running jokes about investors being lemmings who all rush in the same direction, and from an angel investing perspective, it’s definitely not not true. If a deal “feels” hot, it often becomes hot as folks rush to try to get a piece of it before they miss out. The FOMO is real, but I think that good investing requires a steel stomach and willingness to miss out on a hot thing to seek something that you have conviction on.

When you’re investing through AngelList, you’ll get a bunch of information to evaluate the deal beyond just the deal terms, but it’s mostly a function of what the syndicate leads put together for you. There’s almost always a pitch deck from the company (though sometimes it’s very outdated, or from a previous round), and there will always be some sort of investment memo (although from what I’ve seen, AngelList investment memos are a weak approximation of the real things that institutional VCs put together). They’ll usually talk about who else is investing in the deal, what the theoretical market opportunity is, and maybe make allusions to incredible growth or traction. In practice, I find that I mostly ignore the investment memo (I generally interpret it as a sales pitch from the syndicate lead on why I should invest, and I’m very allergic to anything that feels too sales-y, because I understand that the bulk of the lead’s profits will come from my carry), and focus more of my time on the pitch deck.

As a general rule of thumb, I almost always invest only in what I know. More than 50% of the investments I’ve made have been in the data, analytics, or AI/ML spaces. Obviously, this is a little bit antithetical to my goal of wide diversification, but if I’m going to play a stock picker, I can’t really separate wheat from chaff outside of spaces that I’m very deep in. There are a number of benefits to investing in the arenas that I know really deeply:

I generally know who the good VCs are: One of the fastest filters that AngelList investors use is to look at who else is co-investing in the deal. I’ve spent enough time in early stage data/infra startups to have a pretty good sense of which VCs are high-quality (and it’s easy enough to build up this knowledge by looking at who leads the hot rounds in a space). There are definitely certain times when specific names show up, and I’ll nearly blindly invest, because I agree with those people’s investment theses (Mike Volpi and Martin Casado are two great examples of this in data-land, and I also have strong affinities for the Amplify team).

I understand the problem spaces: This is really the biggest key to investing intelligently. If you can look at a pitch deck and be able to say “Yes, this is an approach that makes a lot of sense, and is well differentiated,” it’s a really helpful indicator for whether it makes sense to invest or not. The risk, however, is that there may be a lot of similar companies that you’re not aware of. This gets back to that deal flow problem. In order to make good investments, you need to have a lot of investment opportunities, especially if you’re hoping to make an investment in a specific area.

I can evaluate the profiles of the founders effectively: Because I’ve spent a lot of time in the industry, one of the first things I do, when I see a new deal pop up, is to check out the LinkedIn profiles of the founding team (and any employees they have). I want to understand where they come from, what they’ve done in the past. On occasion, I’ve even gone so far as to do some light backchanneling if I have mutual friends. In the early stages of a business, you’re making bets much more on the team than the product, so I want to know that the people involved are smart and capable.

I’m friendly with VCs who focus on the space: I don’t play this card often, because I value their time, but I’m friendly enough with a number of VCs in the space, and so if I’m really on the fence on a potential investment (usually because I feel like I’ve invested too much recently, and I’m hesitant to dump more money into my angel portfolio), I’ll sometimes ask friends for a gut call, or thoughts on who else is in the space, and how bullish or bearish they are on it.

I do, on occasion, invest in spaces outside of data, though I decline to invest in many more non-data deals than data deals. I know I can’t evaluate those opportunities as well, and so even if I see something that seems attractive, I’ll usually read the pitch deck and move on, unless I have some way to vet it further. A lot of angel investing is just sitting back, consuming the information, and waiting for the deals where you really have conviction.

The reality of it all is that, as an angel investor (on your own), you’ll have a lot less information to go on than an institutional investor, and that’s to be expected. I’m almost always investing the minimum, and certainly not writing million-dollar checks. It’s reasonable to expect that the amount of info that you’ll have access to is likely going to be proportional to the amount of money you’re investing, and if you aren’t comfortable making a decision to invest $1000-$5000 on limited information, you probably ought to rethink whether or not you should be angel investing.