Why Instacart's new 40% lower valuation is actually fantastic for employees

Get thoughts and musings about personal finance and whatever else I find interesting straight to your inbox

Axios, among others, reported recently that Instacart had cut their valuation from $39B to $24B. This feeds nicely into the current macro storyline that the media is telling about how tech startup valuations are being slashed left and right. This is probably true to some extent, but the reality of the situation is that venture firms are continuing to raise massive funds, and once those funds have been raised, the LPs expect them to be invested in short order. The end result is that we may see venture firms being a bit more critical of deals, but we’ll also likely see a very stratified fundraising environment where the hottest companies continue to raise huge rounds out of these massive funds. I do believe valuations will contract a bit, but I would argue that that’s actually a really good thing for employees.

Additionally, Axios calls out a critical observation that I haven’t seen identified in any other major new outlets, which is that the valuation change is actually in the 409A valuation, which dictates the value of RSUs and options that employees receive, but not the price that investors pay for Instacart’s stock. This is actually a really important thing to understand, because it is the difference between this news being a disaster scenario for Instacart, or a boon for its employees.

I’ll explain why throughout the course of this article, but let’s start with a little bit about how the venture markets work, to set the stage.

Startup valuations are a function of supply and demand

The reality on the ground is that with huge new funds being launched, there is still massive demand for startup equity. A frothy market doesn’t negate the fact that VCs need to deploy their raised capital. In fact, rising interest rates and unrest in the world could serve to exacerbate the high valuation problem, since it may be interpreted to herald a second RIP Good Times environment. In that kind of environment, I would expect a feast or famine dynamic. The hottest deals continue to be incredibly competitive, and weaker companies fail faster. A recent LinkedIn post from a GP at Gradient Ventures seems to support this idea, but is even more alarmist, calling out that even good companies may struggle to raise. For companies on the fastest growth trajectories, I suspect they will retain the luxury of setting their own price on their funding rounds. Venture firms queue up, and if the price is one that they’re willing to pay to be in the round, they’re paying up. Venture capitalists still answer to their investment committees, and in turn the fund itself answers to its Limited Partners, so VCs can’t write checks if they are unable to justify the potential upside. But just as inflation has been driving wage increases, it’s driven private valuations higher too.

There are a number of factors that end up determining what valuations investors are willing to pay to invest in a business. One of the more common ways to value a company is applying a multiple based on the company’s revenue. Historically, this might have been a multiple based on a prior year’s revenue. In the current market, valuations are often based on future projected revenue, even though the company hasn’t yet achieved what they claim they are going to achieve. Tomasz Tunguz from Redpoint wrote a post back in November about the 100x ARR multiple, which he describes as “a benchmark for SaaS companies raising rounds” in recent days. If we assume that 100x ARR multiples are becoming the norm, it implies that a company that expects to do $5M in revenue next year is worth $500M today.

Another thing that is important to understand in funding dynamics is that the amount of money raised is a critical input into valuation. In a seller’s market, companies can effectively choose a) how much money they want to take, and b) how much dilution they are willing to accept on their cap tables. Controlling for those two inputs, the company can effectively set the valuation they are targeting. This valuation determines the actual price that investors pay for shares in the company during a funding round. This gets down to simple supply and demand. If there is enough demand in the venture markets, a company will always be able to find buyers for its stock at any price.

Investor willingness-to-pay is often driven by the stage that a company is at. Early-stage investors are often more focused on getting a certain stake in the company (20%, for example), and depending on their excitement level about the founding team and the company’s traction, may be willing to pay more money for that stake. Later-stage investors often shift their thinking towards the potential outcome – how much of a return will they make on the money invested – and will often shoot for a 3x or higher return on their invested capital. What we’re seeing right now, in the market, is early-stage companies receiving much later-stage valuations, which ends up creating an environment where investors take on early-stage risk, for late-stage returns.

Naturally, if there is investor demand at a high price, there is likely to be similar or more demand at a lower price. What we’re starting to see examples of are organizations voluntarily raising less money at lower valuations (if you only click one link in this article, make it this one from David Hsu of Retool). So the real question we want to answer is: why on earth would a company want a lower valuation?

The argument for taking a lower valuation

Big valuations demand exceptional execution (good for company/employees): When you raise money at astronomically high valuations, you set yourself up for a situation where investors expect perfection. If you don’t achieve perfection, investors get frustrated, they can’t get their returns, and eventually, the company has to go back and raise more money, but the terms of that fundraise won’t be nearly as good once the wind is out of the sails. Lower valuations keep expectations more rational, more muted, and give you the flexibility to have a bad quarter here and there. Nobody wants that, but most companies don’t have perfect quarters every quarter.

Lower valuations mean you have more flexibility to show growth: Companies that fundraise at sky-high valuations have to continue growing at an extremely fast pace to continue to justify investors putting in more and more money at increasingly high prices. Bringing on new funding at lower valuations actually gives organizations more flexibility to go back and show growth and momentum. If you can raise at $1B today, and you’re currently valued at $250M, an organization could, instead, choose to raise at $500M, and then $1B, and use both of those as marketing moments, driving sales, recruiting, and employee morale. There’s obviously risk in this – macro conditions could change, taking those larger offers off the table, so there’s something to be said for taking the offer when it is offered, but there’s a tradeoff to be considered.

Less dilution means more value retained for existing shareholders (good for investors/employees): Not every investor will accept investing less money for a lower price, but if your investors really want to be invested, then taking a smaller check will still likely net you the same investors, probably on similar terms. What is important to understand is that, when a fundraising round happens, new stock is issued by the board to sell to the new investors. In most cases of funding rounds (secondary stock sales excepted), this stock appears out of thin air, and is the thing that generates dilution. Dilution basically just means you made more pie from the same amount of dough, which means all the folks who have some percentage of the pie before the dilution have a little less pie after the dilution. In funding rounds, the valuation of the overall company typically goes up, so even though employees and existing investors own less pie, the piece that they own is still going to see some increase in value. By taking less dilution in one round, you effectively enable the organization to defer the dilutive effect of new capital until the stock is even more valuable in the future.

For existing employees, lower valuations mean less tax exposure (good for employees): When you exercise stock options, the IRS tracks your paper gains (specifically, the delta between the current FMV of the stock and the strike price that you paid to exercise your stock). Since FMVs generally only move during funding rounds while a company is private, a funding round that brings a valuation step-up for a company will mean that employees exercising options will have more tax exposure (to be clear for ISO buy-and-hold situations, this is AMT exposure that you may or may not have to pay, but for NSO exercises, this is just straight-up income tax). In some of my earlier articles, I talked about how fast-paced fundings can create really challenging tax situations for employees, and how a lower valuation is a good thing for employees come tax time.

The Instacart strategy: increasing the gap between strike price and preferred to make stock more attractive to employees

The real crux of the Instacart news (and why I believe they’re being very loud about it) is that their new valuation hasn’t decreased the value of the stock to investors, but rather has created more upside for employees who are being granted options and RSUs.

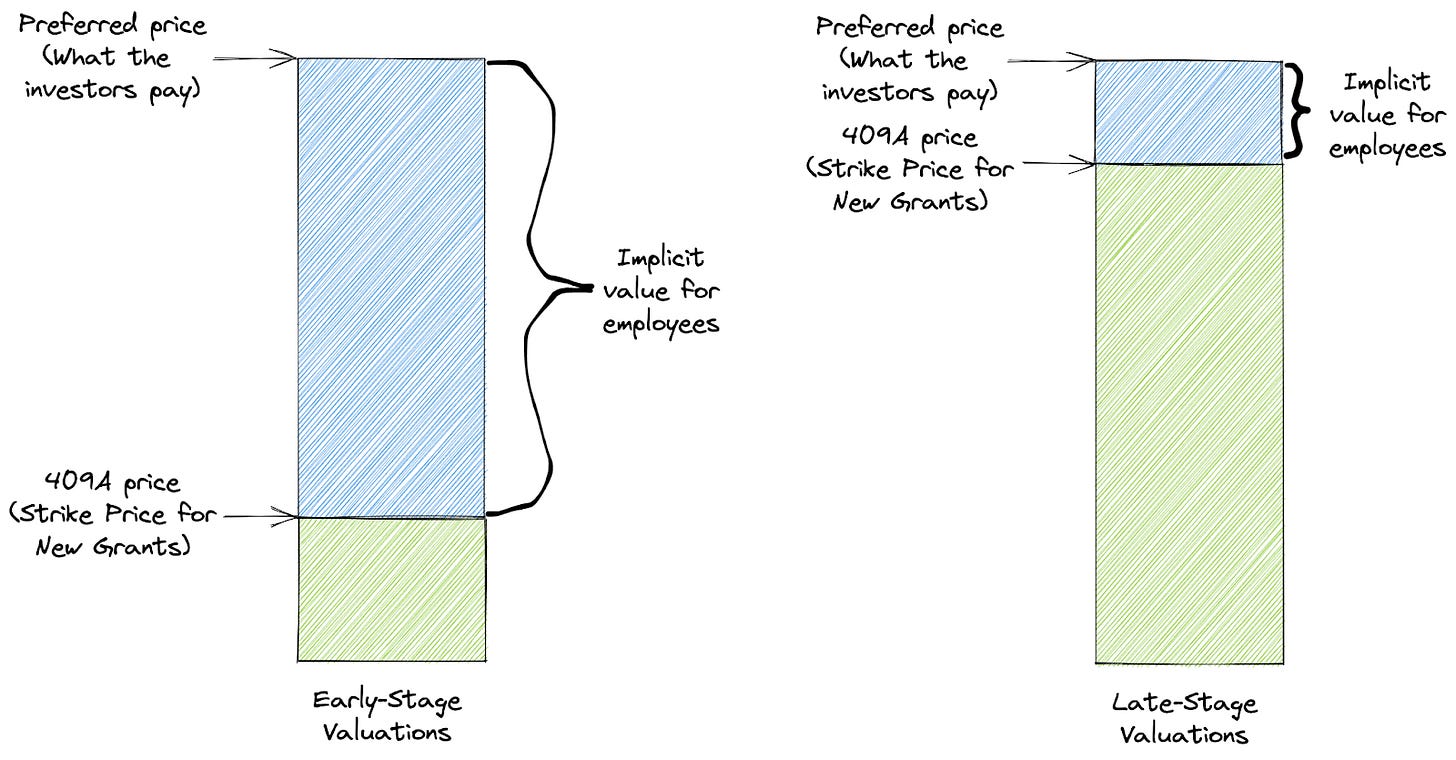

Recall that when VCs invest in a company, they are generally buying newly-issued preferred stock, which comes with benefits like getting paid out first in an acquisition (the exception to this is when investors buy stock in a secondary purchase). Employees, on the other hand, receive common stock. Preferred stock will always have an equal or higher price than common stock, because it comes with those additional benefits. What typically changes over time, as a company matures, is the gap between the common stock price and the preferred stock price. At IPO, the two are equal. Leading up to the IPO, they are very close to each other, but in the early stages of a company’s life, they’re often very far apart, with the 409A price (which determines the strike price) often being 25% or less of the preferred price.

What happened in Instacart’s case was that Instacart marked their common stock to market, and lowered the value of their common stock, which means the company can issue new RSUs and options to employees at a lower price, which creates additional upside for employees. The reason this matters is that a new grant of equity made to an employee has some implicit value from the outset. Specifically, in the case of options, an employee has to pay a strike price to exercise the stock, so the delta between the 409A and the preferred price is what the employee would net if they were to sell a share at the same time that they exercised the share. It’s a little bit different with RSUs, since employees don’t pay for RSUs. Presumably, in this case, Instacart is granting RSUs using a dollar value, and using the 409A price to determine the volume of RSUs granted, which would result in larger volume grants to employees, that, in turn, provide greater upside in a liquidity event.

This difference between preferred and 409A price is really the biggest part of this story. If the story was that Instacart raised outside capital at a lower valuation, that would be a huge blow to Instacart, because that would truly be a down round, where the preferred stock was being valued at a lower price. However, the fact that this is just common stock being reduced in price is actually great for prospective employees, and likely a positive for existing employees (the most valuable of whom will likely be getting refresher grants in short order at a lower price). Tomasz Tunguz of Redpoint even mused that this could become a more common recruiting strategy for late-stage startups.

Speaking from personal experience

I’ve been on both sides of this, both as a prospective hire and a hiring manager. Personally, I’ve always skewed towards earlier stages for when I like to join companies. For me, somewhere between the B and the C round has tended to be my sweet spot. It’s the stage at which I’ve determined I see the right balance of risk and reward – you’re often right at the beginning of the hyperscale growth, but still early enough that a well-placed bet can result in an easy 10x value increase on options. That said, I’m looking for companies at that stage with valuations that feel sane, and like the company can grow into those valuations in 1-2 years, so that I can realize that 10x upside. When companies recognize a lot of future growth early on, it creates a dynamic for employees where the risk-reward ratio becomes skewed in a way that doesn’t necessarily benefit employees.

The true call-to-action for employees here is to think critically about your company’s valuation (or the valuation of the company you’re considering joining), and realistically think through how much upside exists at any given valuation, and evaluate the risk/reward. There’s no right answer here, and for some, a higher valuation brings comfort and confidence, and for others, it may represent limited opportunity.