My product management story

Musings on what it was like to move into product from sales engineering

If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can get thoughts and musings about personal finance and whatever else I find interesting straight to your inbox by clicking here:

Product Management is a funny discipline. What you do as a product manager varies wildly from company to company, and what it looks like is heavily influenced by the culture of the organization. There are many routes into product management, as a new-grad going into APM programs, or as a recent MBA, and as a highly cross-functional role, many people make lateral moves into product management from other disciplines. Personally, I made a career transition a few years ago to get into product management, after about a decade of pre-sales and software engineering roles. This is my story about how, and why, I made the leap.

Motivations

For years, I was determined that I would never be a PM. Frankly, until I became a PM myself, I didn’t really understand what they did. As an engineer, I barely worked with them. My first job out of college had one PM for the entire engineering team (which was north of 20 engineers). My second engineering gig, there was a PM attached to some of the work I did, but he seemed much more interested in impressing executive leadership with his Powerpoint skills than being involved in the actual product roadmap. As a sales engineer, I felt plagued by PMs who wouldn’t publicly talk about roadmaps, who couldn’t explain rationales for our product direction, and who existed primarily to tell me “no.”

From the outside looking in, it looked like a mercilessly thankless job. Engineers got all the credit for building the cool thing. Salespeople got all the credit for selling the big deal. The PM is relegated to the back of the party, left just to cheer everybody else on. Operationally, PMs are often the punching bags. Bearers of bad news, harbingers of delayed delivery, messengers of descoped features. Before I stepped into the role myself, I frequently found myself in situations where I was furious for not getting the features that I felt were critical to selling my next deal. As someone who spent most of my career in sales, and thrives on public recognition, this looked like torture.

What changed my perceptions was a leap of faith, in 2014, to join a company as the first employee. There was no product, no engineers, just two co-founders and a would-be sales engineer, if we’d had a product to sell. We ended up spending about three months validating our market, conducting customer development interviews, and identifying the bedrock that we would build our company on. As we hired engineers, and grew the business, I settled into a standard pre-sales role. As the first technical member of the go-to-market team, I predated a formal product management function. I fell into a role of being the primary point-of-contact in the field, talking to users and buyers day-in, and day-out, and ended up incidentally defining a lot of the early roadmap based on my customers’ needs.

After a four year stretch, I found myself ready to move on, but craved a return to the early excitement of helping to define the roadmap and figure out the next big thing for the company. I felt like I had product intuition, but I still didn’t really have a good understanding of product management as a role. But, at the very least, I was definitely product-curious, and I felt like I needed to pull on the thread to see where it led.

What does a product manager even do?

I’d worked with PMs over my years as a pre-sales engineer, but most of the companies I’d been an actual engineer at, I’d had limited interaction with product managers, and so I’ll admit, I had a pretty vague understanding of what they did. I set out to find the answer by digging in, doing research, and asking my network.

Somewhat ironically, my natural inclinations when I want an answer to a question are to get information from a lot of people and build up my own picture and mental model of what the answer is. This ends up aligning really well with how the job typically manifests, but I didn’t know it at the time. I’m pretty good at networking, so what I did to start researching was to reach out to a number of VPs, SVPs, CPOs, and current PMs to ask them what the job actually entails.

This was a very intentional period of exploration. I had a few motivations with this conversations:

Figure out what the heck a PM does

Figure out if I actually want to do this thing

Start to build relationships with potential hiring managers

As I started talking to people, there were some interesting patterns that started to emerge from my conversations:

Product Managers use a ton of jargon

When I started talking to people in product, immediately you start to hear words like hypothesis and validation and testing and experimentation. The language of product management is very scientific, and I wasn’t expecting it at all. They often sound like they’re setting up lab experiments, although it’s probably more often an exercise in psychology or anthropological research.

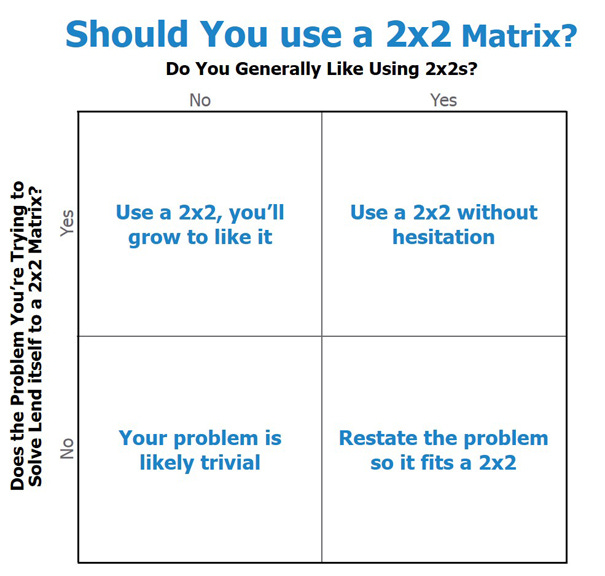

Frameworks and frameworks

Nearly every product leader I talked to mentioned frameworks (and at the time I had no idea what a framework even was, although now I would probably define it as a tool for making a specific type of decision). One leader went so far as to say that product management is really just having a bunch of frameworks in your bag of tricks and knowing when to use each one.

Nobody has a standard definition for what a PM does

I think I talked to 7 or 8 people with VP/C-level titles, and the one question I asked every one of them is: “What does a PM do?” I got as many answers as people I spoke to. This goes back to what I mentioned in the intro, which is that PM looks wildly different from company to company, and so it makes sense. It’s a much more purpose-built role, so it makes sense that it varies, but this also has some pretty big implications in terms of what it’s like to interview and get hired.

A major reason I eventually decided to pursue product management was that I recognized that effective PMs need to be highly skilled in influencing others, and making highly-rationalized decisions. These were both skills that I identified as important to my long-term career growth, and skills that I felt like I wasn’t very good at, so helped me get clearer on why I wanted to make the transition.

Role and company

One of the most challenging bits of my transition into product management was how I was doing it. A common rule of thumb is that within the space of role and company, you only want to change one at a time. It’s a lot trickier to do both simultaneously, because you don’t have a track record for a new company to look back at. This was a common thread through the discussions I had with product leaders -- the easiest way to make a shift into product management was to shift roles laterally at the same company, and get some time in the seat before moving to a new company. However, the opening for the role didn’t exist at my current company, and after four and a half years there, I was ready to move on.

As a result, it was a long job search. Probably six months or so of looking for the job. My approach to researching the role helped a lot, because it gave me an opportunity to meet the hiring managers an establish enough a rapport that I could get into the interview process without getting stuck in the black hole filter of a recruiter who would inevitably look at my resume and determine that I didn’t have the appropriate qualifications. Even so, I had a lot of doors shut in my face. One company I interviewed with did me the lip service of setting me up with a couple product VPs, who after an hour of chatting, advised me that I didn’t think like a product manager, and that as a policy, they don’t hire people into the role who haven’t already done it. They politely pointed me towards their customer success organization. (I will say that one of these VPs has actually remained super helpful as I’ve made the journey into PM, and given me great advice along the way, so don’t assume that a no means they don’t respect the hustle!)

There were also a lot of interviews that I would qualify as “cannon fodder.” One of the nice things about meeting all the product leaders during my research phase was that I got opportunities to hone my pitch for why I wanted to be in product, and smooth out the story line. So much of getting a job is how you pitch yourself...you’re the product. Even with that practice, the first phone screen I had for a PM role was abysmal. I distinctly recall being asked really basic questions about why I wanted to move into product, and just stumbling over my words, not being able to effectively spin the yarn of my story, and unsurprisingly, I didn’t move further in the process.

Can I even afford to take this role?

As I started to get more serious about interviews, something that ended up causing me a lot of heartburn was compensation. I was coming from a sales role, and for better or for worse, sales people make some of the best money in a startup, especially if they’re hitting their quota, or getting beyond their quotas. I’d done some research on PM compensation, and knew that there was a chance that my compensation, as an entry-level PM, might be as much as a 30-40% paycut for me. It was really stressful knowing that I was spending all of this energy trying to get a job, and there being a chance that I couldn’t even afford to switch jobs.

I did end up having to take a paycut, but it ended up being much smaller than I thought it might be (around 20%) and I was able to negotiate a signing bonus that blunted the impact in the first year. The key to reducing the risk here ended up being a well-crafted narrative around why my prior experience as a pre-sales engineer actually made me really well-qualified for product work, and leaning on the early days of StreamSets to convey the product work that I had done (albeit not with the title). I was also able to play a handful of offers off of each other -- I had some backup pre-sales offers, which came in at much higher compensation numbers (unsurprisingly), and was able to use those to leverage up my product manager offers.

Natty, Product Manager

In the end, I got a role as a product manager that I was really excited to have, and joined the team at Heap. Ironically, my first product manager role was actually building products for other product managers, which ended up being a bit of a force multiplier for me. Imagine your job being to call up other PMs to ask them how they do their job, and being able to try to identify ways to improve their work, while also taking notes on the side about how I can improve my own game. That said, becoming a real product manager was a major shock to the system.

My pleasure centers needed rewiring

As a sales engineer, what gave me joy was solving a problem for a customer, or having a meeting where the message just resonated really well, or winning a hard-fought deal. The things that made the job fun came fairly fast and frequently, as we were always having intro calls, and I was always having new conversations. With product management, the pace can be much slower. It takes time to define a feature, and it takes time for engineering to deliver it, and it takes time for it to actually impact a customer and drive new business. It’s much slower-paced, and so I had to figure out new ways to get joy out of the job. What I’ve ended up finding I enjoy the most is research conversations, and digging into data. Learning something new, especially something I wasn’t expecting, has become the new killer discovery call for me, so to speak.

Your customer-base just got a lot more complex

Having spent eight or so years focused on external customers, my natural instinct is to orient around external customer needs. The reality of product management is that your customer-base is now external, but also very internal to the organization you work at. The engineering team is your customer, the marketing team is your customer, the go-to-market team is your customer, the support team is your customer, the leadership team is your customer. Pretty much everybody at the company is going to have some stake in your work, and so it’s crucial to think of them, and treat them as customers (not in the sense that the customer is always right, but that you serve their needs and wants, as well as your external customers’, and you’ll need to weigh all of their needs when prioritizing work).

It’s not fun to say no, but it’s part of the job — Communicate the why

I hate telling people “no,” and product managers have to do that a lot. Product management demands a brutally difficult balancing act to ensure that the new features get built, existing features get improved, and tech debt gets paid down. For everybody who’s ever cursed a PM under their breath for not giving them what they want, let it be known that generally we want those features too. We take the job because we want to delight our customers and users. But it’s impossible to please everyone, and the responsibility often falls to us to decide what ends up above or below the line, and, all too often, the job requires ruthless prioritization. Every PM will have a different stylistic way of communicating those “no’s,” and I prefer to try to rationalize them and always be hyper-communicative about why I have to say no, or why schedules are shifting. What drove me nuts on the sales engineering side of the fence was hearing “no,” and not being able to understand why a decision was made. “Why” is such a powerful concept. Don’t forget to use it.

Lots of responsibility, very little authority

Product teams have pretty varying levels of influence and control, depending on how the organization is structured. A lot of companies are very engineering-led, or sales-led. In both of those cases, the product team is still responsible for ensuring that the product gets to where it needs to go to be successful. Some folks will say “the product manager is the CEO of the product,” but I think it’s a bit of a fallacy, because you don’t have hiring and firing authority, like the CEO does. The engineering team doesn’t report to you, and if they don’t trust you to make good decisions, they’re not going to follow your lead. Establishing credibility is critical to product success. I feel super lucky to have a technical background, so I can speak the same language as the engineers (though you’ll rub people the wrong way if you step over the line and get too prescriptive about solutions or architecture), and I also empathize strongly with the sales and marketing teams, having been in those seats for a long time. The more trust you command within your organization, the more success you can see. On some level, product management really is a sales role, but you’re usually selling your ideas and direction to the business to align it on the direction you believe the company needs to head.

Imposter syndrome is real, and product can be lonely

I wasn’t prepared for the amount of imposter syndrome I would feel, and how lonely product sometimes gets. As a sales engineer, I was almost always a part of a team of folks working on the same types of problems, and we could easily share tips and tricks and help each other out, or swap in on accounts where we needed to. Product is a much different experience. Product organizations don’t scale rapidly, because there’s typically one PM for a functional area, or the number of PMs is determined based on a ratio of engineers that they work with. As such, there’s fewer people on the team, and oftentimes other members of the product team are dug heavily into their areas of the product, and there may be less communication across functional areas, or just less visibility. It’s also a lonelier job, as PMs tend to be responsible for their product area, without a lot of redundancy. As I mentioned, I don’t think it’s correct to call PM a CEO-like role, but the notion that CEO is an extremely lonely job is certainly relevant in the context of the PM role, as well. For whatever part of the product you manage, the buck stops with you.

I’d do it again

It’s been extremely humbling to go from a decade of career growth in a particular role, and then go back to being essentially an entry-level individual contributor. It’s been a stark reminder of the fact that you just don’t know what you don’t know.

As many warts as the role can have, it’s also a really gratifying role. It’s really energizing to spend tons of time researching a problem area, and then have your ideas validated by customers and users. And the feeling of getting a feature out the door that you’ve been working on and shepherding for months is a really cool feeling. There’s also so much variety to the role. If you’re someone who gets bored easily, product management will keep you busy, always, but it does require a lot of self-motivation. Once you get past the early stages of the role, no one’s going to be looking over your shoulder to tell you to build a particular thing, and it’s imperative for you to go and ask questions and be curious and figure out where the product should go next. It’s a role that requires complex, deep thought, to make tactical decisions, as well as strategic ones.

In spite of the challenges and the roller coaster of a role that product management can be, I’m continuing to move forward. I set out to move into this role with very specific goals in mind, and I feel like spending time in the product management seat has paid dividends on dividends, in terms of making me more effective organizationally, and more effective in driving business value. It was a tough road getting here, and it’s a tough road being successful in the role, but I’d definitely do it again.

Very Interesting insights. Thanks for putting it down into words.

Very interesting - enjoyed "following" the journey from your perspective