If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can get thoughts and musings about personal finance and whatever else I find interesting straight to your inbox by clicking here:

My wife and I are avid readers of Matt Levine’s Money Stuff newsletter (if you’re not subscribed to that, and you generally like the things that I put out, it’s definitely worth a look). The other day, they had a section discussing a recent ProPublica (which has been on a roll, writing some incredible pieces about how the uber-wealthy wiggle out of tax burden) article about Peter Thiel’s $5B Roth IRA. Before I get into any more detail, I’ll say that I’m absolutely a believer in paying your fair share in taxes, but hot damn is this a crazy tax sheltering maneuver.

The Humble, but Mighty Roth

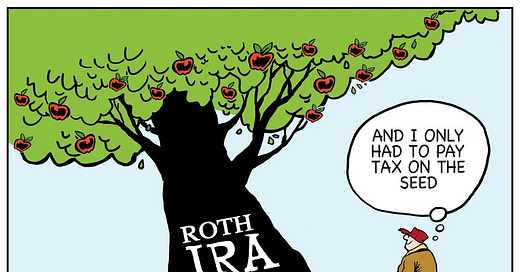

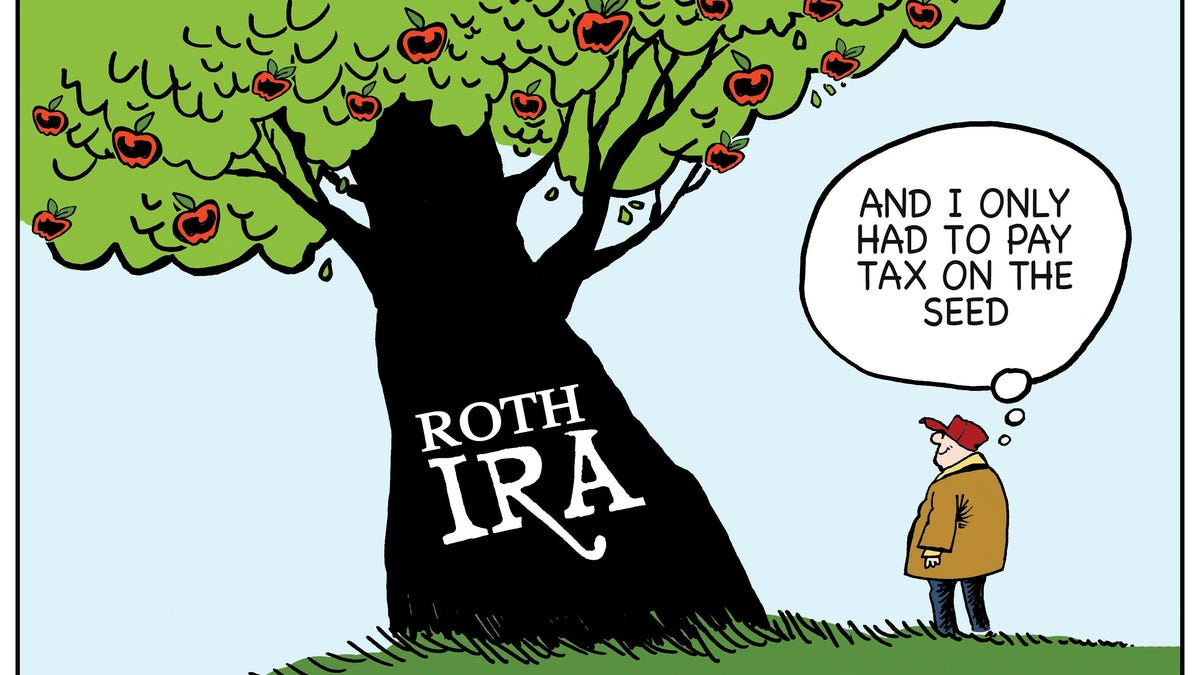

One of my biggest personal finance regrets and mistakes was not learning about the Roth IRA when it was an option open to me. With traditional IRAs, which are available to anyone at any income level, you’re allowed to contribute in pre-tax earnings (up to $6000 per year, thereby reducing your taxable burden). The funds can be invested and traded, without having to pay taxes. Once you hit 59 ½, you can start withdrawing them but you have to pay income tax on any withdrawals. Roth IRAs are tax optimization machines, and differ from traditional IRAs, in that you contribute after-tax earnings (again, up to $6000/year), but then never pay taxes again. Once you hit 59 ½, you can withdraw the earnings, tax-free. It’s a compounded growth dream.

As the ProPublica article points out, “The late Sen. William Roth Jr., a Delaware Republican, pushed through a law establishing the Roth IRA in 1997 to allow ‘hard-working, middle-class Americans’ to stow money away, tax-free, for retirement.” The whole point of the Roth was that it was expressly not a vehicle for rich people to avoid taxes, and so there were income limits put on contributions to Roth IRAs. As an individual, you can contribute $6000/year into a Roth if you make $125,000 or less per year, and that starts scaling down to $0 allowable once you hit $140,000 in income. Unsurprisingly, that means most tech workers (probably including most software engineers straight out of college) are never eligible to contribute money into a Roth IRA.

And yet, Peter Thiel managed to sock away a whole huge chunk of his PayPal founder stock into a Roth IRA, and turn that into a $5B tax haven that puts Caribbean offshore accounts to shame. How in the hell?

Backing into a Roth IRA

Clearly, the income limits didn’t stop Peter Thiel from getting a bunch of cash into a Roth IRA, so you might ask yourself: how did he manage to fund his Roth? Now, I don’t know much about his lifestyle in the founding days of PayPal, but there are some plausible assumptions to be made about how this probably went down.

The likely scenario, and the one that probably describes how most founders would approach this sort of tax strategy, is that founders simply don’t pay themselves much money. Stock generally gets divvied up between founders at time of incorporation, and if you don’t have VC funding in that first year, there’s a good chance you’re not paying yourself anything. Even after you take venture money, most founders pay themselves pretty aggressively below-market wages. The standard rule of thumb I’ve heard from founders I’ve spoken with is that they pay themselves just enough that they’re not worried about making ends meet, but not a penny more. If you’re young and single, or at least, not supporting a family, that number might be below the $125,000 income limit, even in the Bay Area. That means if founders have a year of low income, perhaps in the middle of their career, they can open up a Roth IRA and contribute in a tax year when they have unusually low income levels.

There’s also another way you can get a Roth IRA opened, even if you make more than the $140,000 limit on any contributions. In 2010, a change to Roth IRAs took effect, which had actually been enacted several years earlier in a reconciliation act, that removed the income limit on Roth conversions. Since Roth IRAs came about much later than traditional IRAs, the original law included provisions to allow people to convert their traditional IRAs into Roth IRAs by paying income tax on the converted amount, provided they met the Roth income limitations. The 2010 change means that anybody, at any income level, can convert traditional IRA funds to Roth IRA funds (often called a backdoor Roth IRA) by paying a one-time tax hit. The other easy way that people above the income limit end up with Roth IRAs is by making Roth contributions to a 401(k). Not every 401(k) plan offers this, some 401(k) plans will allow you to specify whether you want your contributions to be pre-tax (traditional) or post-tax (Roth), and your income level has no bearing on whether or not you have this option -- it’s solely dependent on what the 401(k) plan offers. Any Roth contributions you make can be rolled over into a Roth IRA once you leave a company.

Understanding a bit about founder stock

Being very candid, I’ve gone through periods of founder flirtations, where I thought I might go off and try to start something (I’ve gotten as close as working through a incorporation application, but never actually pulled the trigger), and knew my income would drop like a rock. If I did, you can be sure that one of the first things I’d do would be to start a Roth conversion. However, before this ProPublica article, I’d never even had the faintest thought of buying founder stock with a Roth IRA. I can understand and appreciate the scathing tone that ProPublica takes, because it’s a pretty audacious move, but it’s also an incredible manipulation of the tax code.

The thing that makes this all come together is the fact that founder stock is essentially “worthless.” Founder stock isn’t actually anything different from what employees get when they exercise options (it’s still just common stock, typically, though sometimes has special provisions around voting rights), but they get a lot more of it than employees, and they buy it when the price of the stock is a lot lower. When founders incorporate, and issue stock to themselves, they don’t get it for free. They do actually pay the company to purchase that stock, but at time of founding, the initial price of the stock is usually pegged at some fraction of a penny. When I joined a company at the seed/pre-seed stage, my restricted shares cost me $0.0001 per share. That’s not a typo. Most companies, at founding, issue about 10M shares to the founders (just to be a nice round number). If PayPal, with its six founders, issued equal stock to each of its founders, they probably bought the entirety of their founder stakes at a cost around $1,666, depending on where they set the initial price per share. Easily an amount that can fit into a Roth IRA in a single year.

There’s actually a whole bunch of reasons why a founder might not want to do this, the biggest one being that most founder equity in tech startups will qualify as qualified small business stock. Since QSBS is federally tax-free after five years, founders might not need the IRA tax haven if they have a modest outcome. However those major tax breaks only extend to the first $10M in capital gains, and you’ll owe tax on gains past that, so I guess if you expect to be building a multi-billion dollar business, it makes sense to hang onto some of your stock outside of an IRA and some of it inside an IRA? Or, if you already happen to be independently wealthy, maybe you just don’t need any of those funds until retirement anyway. Either way, if you find yourself in a situation where you feel it’s critical that you buy your founder stock in an IRA, you probably either a) have a lot of hubris/ego/overconfidence to assume that you’re going to have an exit that generates more than $10M in gains, b) know something the rest of us don’t about your business, or c) don’t need the money anytime soon, and have nothing to lose by making the bet.

Sheltering alternative investments in SDIRAs

Consider this your fair warning that I’m not 100% clear on exactly how you do this thing, and there’s a whole bunch of question marks and legally gray areas where you could run afoul of the IRS (which is probably a bad idea, especially now that they’re going to be getting a whole chunk of investment to audit tax-dodgers), and also I’m not a CPA or a tax attorney so be very clear that none of this is tax advice. The lynchpin of the maneuver is an investment vehicle called a self-directed IRA (SDIRA). Self-directed IRAs can come both in Roth and Traditional flavors, like a normal IRA, but where non-self-directed IRA funds can typically only be invested into publicly-traded securities, SDIRAs can be used to invest in a whole host of alternative investments like precious metals, real estate, and, you guessed it, privately-held companies.

AngelList, for example, allows you to invest in private companies via a partnership they have with Alto IRA. When you make an investment, you can choose to direct the funds to come from an Alto-managed SDIRA. I’m actually an LP in a small fund via an SDIRA opened with Strata Trust, and the process was relatively simple. Fill out some paperwork, liquidate some assets in my traditional IRA, and transfer them over to Strata Trust, and then Strata acts as the custodian for an SDIRA that I direct the investment for. This generally works quite well, because IRAs can invest in C-corps, which are almost always how tech startups are structured from a legal entity perspective. Generally, to invest an SDIRA directly into a company probably requires that company to be willing to allow the investment through that vehicle, but if you’re the founder of that company, I’m guessing that’s not a terribly hard thing to make happen.

No self-dealing allowed!

Where this gets really hazy, however, is with IRA rules around self-dealing. The US tax code prohibits the purchase of certain assets within an IRA, and one of the major areas of prohibited transactions are around purchasing assets that benefit the owner themselves. For example, you can hold real estate through an SDIRA, but you can’t use or live in that real estate while it’s held by the SDIRA, because that could constitute self-dealing.

In Peter Thiel’s case, he purchased stock in a company that he was the founder of. So he can directly influence the direction of the company, and thus the outcome of his equity. So is this self-dealing? If we look at the US tax code, and get really in the weeds, the determination of whether a transaction is self-dealing depends on whether the transaction would be to the benefit of a “disqualified person.” In particular, a couple definitions of disqualified persons apply:

A direct or indirect owner of 50% or more of the company’s stock

An officer, director, or 10% shareholder in the company

Since Peter Thiel was one of six founders, it’s extremely unlikely that he held more than 50% of the company’s stock, but he was the CEO of PayPal, so was definitely an officer, probably a director, and likely at time of stock purchase, more than a 10% shareholder. While the definition of the first disqualification is pretty crystal clear in the tax code, the second one reads a bit more circuitously, and seems like it could be read as either “no officer, director, or 10% shareholder” or “no officer, director, or 10% shareholder of an entity that is a 50% owner in the company.” While I’m not entirely clear on how to read the language properly for the second definition, there is definitely legal precedence to allow these transactions to occur.

The other wrinkle is that the transaction might be prohibited if you purchase the stock at a below-market rate. If the transaction favors you in a way that wouldn’t be available to anybody else, it’s likely that it would fall under the prohibited transaction provisions. This forces the question of: what is the fair value of a newly-founded company? The answer to that question becomes a lot more rigorous once institutional investors start buying stock, and as the company operates, as 409A valuations are used to determine what the fair market value is (which is still often far below the valuation that investors purchase equity at, but is at least supported by independent audits). At incorporation, however, it’s exceedingly hard to determine what a reasonable valuation should be, but to say that the whole company is worth $10,000 or even $1,000 definitely is eyebrow-raising.

Surprisingly legal

It’s worth noting that the government has been aware of some of these loopholes for some time, and raised yellow flags around them. In 2014, the GAO released a report recommending that Congress revisit its legislative vision for IRAs. It alludes to the fact that the IRS forgoes nearly $15B per year, and that number will get a lot larger as financial cowboys like Thiel get to retirement age. However, in spite of all of the gray areas, the approach here seems to pass legal muster. Not only did Thiel manage to make it through an IRS audit unscathed, his PayPal cofounder, Max Levchin, managed to repeat the feat at both PayPal and Yelp. It’s extremely clever financial engineering, although morally and ethically ambiguous, for sure. Pair your fair share, folks.